Air Quality Improvement in Colombo due to COVID curfews or changes in wind?

By Lareef Zubair and P. Ellegala

Federation for Environment Climate and Technology

Kandy

Reports on drop-in Air Quality Index being due to curfew

There are a growing number of air pollution measuring stations in Sri Lanka that observe air pollution. Of these the index called Air Quality Index (AQI) is tied to the amount of fine particulates of size of 2.5 microns (pm2.5) and to other pollutants such as Ozone (O3) and Nitrous Oxides (NOX). The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), National Buildings Research Organisation (NBRO), US Embassy (USEMB), National Institute of Fundamental Studies (NIFS), and our organisation (FECT) measure pm2.5.

The Air Quality instrument at the US embassy in Colombo 7 is the most reliable instrument in Sri Lanka presently. If one compares the USEM measurements for pm2.5 the week before and after the curfew (March 20), we see no perceptible drop. If one compares the pm2.5 to 2 to 4 weeks before and after, then there is a drop off of around 30% - significant but not overwhelming.

Sometimes, the drop off of pm2.5 between February and April 2020 of 50% is presented as evidence of the dominant role of curfews. However, such a comparison includes the influence of the intervening wind reversal. There was a similar large drop off from February to April in 2018 and 2019, as seen in the chart, even without the curfews.

We can attribute the dominant cause of the drop-off to seasonal reversal in wind. The reversal in wind directions in April shuts down pollution transport to Colombo from most sources.

From November till March, the wind comes from North and East carrying with it pollutants from the Indian Sub-continent and South-East Asia. As the air tracks over the Sri Lankan landmass, then it adds to this pollution from Norochcholai coal burning, forest fires, agricultural residue and garbage burning and other industries. From April to September, the wind reverses so that on average the wind direction is coming from the South and West over the pristine atmosphere of the Indian Ocean. Even though the air pollution drops in Colombo from April to September, the wind reversal takes the pollution from the Western coast to the rest of Sri Lanka. Persuasive studies from the Universities of Peradeniya and Sabragamuwa show that the forest dieback in HortonPlains is tied with a rise in pollution from April to October lead contamination in the soil. This rise is likely related to the transport of atmospheric lead from Western Coast.

Daily variability in wind trajectories

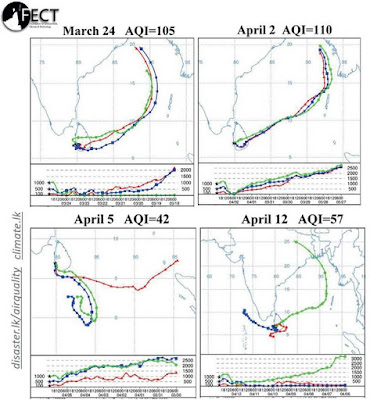

While what has been described are seasonal average wind patterns, there is day to day variability that affects the details of local pollution. Based on observations of wind, we have computed trajectories of air that reaches Colombo on each day before, during and after the curfews. The accompanying maps shows such trajectories for the two days with the highest and lowest AQI during the curfews. These maps show that when the wind comes from North and East then air pollution is twice as high as when it comes from the South and West.

Maps: Shows the trajectories of air masses at different heights that arrive in Colombo on days with high AQI (top - March 24 and April 2, 2020) and low AQI (bottom row - April 5 and 12, 2020). The red, blue and green shows the history of air masses for six days before it arrives at 100 m, 500 m and 1000 m elevation over Colombo.

Sources of Air Pollution other than traffic

Traffic and the shut down industries do contribute significantly to air pollution but it is secondary to the combined effect of other factors the role of which are manifested by the wind reversal in April. These major sources are:

Transboundary Transport of Pollution: The maps shown here show that there could be transport of pollution from the Indian sub-continent and Northern South-East Asia to the extent of doubling of AQI. Even previously the perceptible rise in air pollution in Colombo from 3-5 November 2019 were on days where the air pollution levels in Northern India was high and where the air arrived in Sri Lanka from over New Delhi, Kolkata, the Bay of Bengal, the Western Coast and over Norochcholai.

Forest, Scrub and Agricultural Residue Burning: Forests and grass land are dry in March and there is agricultural byproducts after the end of the Maha season. There is setting slash-and-burn for chena in a controlled manner. Setting fire to dry tinder is sometimes a prank and sometimes for short term gain. There is no monitoring and regulations in place and thus little appreciation of the air pollution among other impacts.

Poor solid waste management systems and the availability of cheap cooking gas has resulted in rural and urban dwellers incinerating unnecessarily. There is a sense that sending something into the atmosphere is a cost-free waste disposal.

The Norochcholai Coal Power plant (NCPP) spews 5000 kg each day into the atmosphere when it is running perfectly - on days with defective air purification equipment or with unscheduled shut down or startup, it can emit much more. The emissions from the NCPP are generally directed towards the Western Coast and Hills from November to March and to the North-Western, Central, North-Central, Eastern and Northern Provinces from April to October. In transition months these seasons, some component gets dispersed over large areas. There can be much better focus by the CEB and its regulators on following the environmental regulations in place.

Summary

The curfews in Sri Lanka and in the larger region contributed to a significant drop in air pollution. The role of curfews was overshadowed by the seasonal reversal in wind as happens in monsoonal regions. There has been an inexorable rise in air pollution in Sri Lanka. Experts have claimed that even the present levels of air pollution could lop off several years of the life-span in humans and animals. The efforts of the mandated institutions has not reversed the decline in Air Quality.

We should monitor, raise awareness among the public and pressure lax polluters responsible for major sources of air pollution. The emissions testing for vehicles has helped. Mitigation options are available for other sources and should be pursued. For example, it will be a blunder to add a new coal plant as coal is the worst option for emission. We need to learn from the then promises of “clean coal” at Norochcholai, the switch to outdated technology, the subsequent failure to monitor as required in the EIA, and the failures of the regulators under pressure on and of politicians.

In a time where COVID-19 threatens our respiratory health and has overloaded the health services especially related to respiratory ailments, monitoring and mitigation of air pollution must be a moral priority.

Federation for Environment Climate and Technology

Kandy

Reports on drop-in Air Quality Index being due to curfew

News reports, feature articles and social media posts have attributed the recent improvement in air quality to the curfews since March 20. These reports seem to follow news in locations such as Southern California or in Central China where the pollution had dropped by 70%. However, the casual surmise that if one shuts down traffic and closes down the majority of industries and then we shall have better air quality can set us back if it is not accurate, as we shall lose sight of the role of pollution from other sources.

These include:

- Trans-boundary Pollution particularly from the Indian Sub-Continent

- Forest Fires, Garbage Incineration, Agricultural Residue Burning

- Norochcholai Coal Power Plant

Industries that continued to function

The relative contributions of these sources varies by place and time. We make use of the available observations of air pollution to address the question of whether it was only the shut down of traffic that led to drop down.

Instrumental measurements in Sri Lanka

There are a growing number of air pollution measuring stations in Sri Lanka that observe air pollution. Of these the index called Air Quality Index (AQI) is tied to the amount of fine particulates of size of 2.5 microns (pm2.5) and to other pollutants such as Ozone (O3) and Nitrous Oxides (NOX). The Central Environmental Authority (CEA), National Buildings Research Organisation (NBRO), US Embassy (USEMB), National Institute of Fundamental Studies (NIFS), and our organisation (FECT) measure pm2.5.

The Air Quality instrument at the US embassy in Colombo 7 is the most reliable instrument in Sri Lanka presently. If one compares the USEM measurements for pm2.5 the week before and after the curfew (March 20), we see no perceptible drop. If one compares the pm2.5 to 2 to 4 weeks before and after, then there is a drop off of around 30% - significant but not overwhelming.

Sometimes, the drop off of pm2.5 between February and April 2020 of 50% is presented as evidence of the dominant role of curfews. However, such a comparison includes the influence of the intervening wind reversal. There was a similar large drop off from February to April in 2018 and 2019, as seen in the chart, even without the curfews.

We can attribute the dominant cause of the drop-off to seasonal reversal in wind. The reversal in wind directions in April shuts down pollution transport to Colombo from most sources.

From November till March, the wind comes from North and East carrying with it pollutants from the Indian Sub-continent and South-East Asia. As the air tracks over the Sri Lankan landmass, then it adds to this pollution from Norochcholai coal burning, forest fires, agricultural residue and garbage burning and other industries. From April to September, the wind reverses so that on average the wind direction is coming from the South and West over the pristine atmosphere of the Indian Ocean. Even though the air pollution drops in Colombo from April to September, the wind reversal takes the pollution from the Western coast to the rest of Sri Lanka. Persuasive studies from the Universities of Peradeniya and Sabragamuwa show that the forest dieback in HortonPlains is tied with a rise in pollution from April to October lead contamination in the soil. This rise is likely related to the transport of atmospheric lead from Western Coast.

Daily variability in wind trajectories

While what has been described are seasonal average wind patterns, there is day to day variability that affects the details of local pollution. Based on observations of wind, we have computed trajectories of air that reaches Colombo on each day before, during and after the curfews. The accompanying maps shows such trajectories for the two days with the highest and lowest AQI during the curfews. These maps show that when the wind comes from North and East then air pollution is twice as high as when it comes from the South and West.

Maps: Shows the trajectories of air masses at different heights that arrive in Colombo on days with high AQI (top - March 24 and April 2, 2020) and low AQI (bottom row - April 5 and 12, 2020). The red, blue and green shows the history of air masses for six days before it arrives at 100 m, 500 m and 1000 m elevation over Colombo.

Sources of Air Pollution other than traffic

Traffic and the shut down industries do contribute significantly to air pollution but it is secondary to the combined effect of other factors the role of which are manifested by the wind reversal in April. These major sources are:

Transboundary Transport of Pollution: The maps shown here show that there could be transport of pollution from the Indian sub-continent and Northern South-East Asia to the extent of doubling of AQI. Even previously the perceptible rise in air pollution in Colombo from 3-5 November 2019 were on days where the air pollution levels in Northern India was high and where the air arrived in Sri Lanka from over New Delhi, Kolkata, the Bay of Bengal, the Western Coast and over Norochcholai.

Forest, Scrub and Agricultural Residue Burning: Forests and grass land are dry in March and there is agricultural byproducts after the end of the Maha season. There is setting slash-and-burn for chena in a controlled manner. Setting fire to dry tinder is sometimes a prank and sometimes for short term gain. There is no monitoring and regulations in place and thus little appreciation of the air pollution among other impacts.

Poor solid waste management systems and the availability of cheap cooking gas has resulted in rural and urban dwellers incinerating unnecessarily. There is a sense that sending something into the atmosphere is a cost-free waste disposal.

The Norochcholai Coal Power plant (NCPP) spews 5000 kg each day into the atmosphere when it is running perfectly - on days with defective air purification equipment or with unscheduled shut down or startup, it can emit much more. The emissions from the NCPP are generally directed towards the Western Coast and Hills from November to March and to the North-Western, Central, North-Central, Eastern and Northern Provinces from April to October. In transition months these seasons, some component gets dispersed over large areas. There can be much better focus by the CEB and its regulators on following the environmental regulations in place.

Summary

The curfews in Sri Lanka and in the larger region contributed to a significant drop in air pollution. The role of curfews was overshadowed by the seasonal reversal in wind as happens in monsoonal regions. There has been an inexorable rise in air pollution in Sri Lanka. Experts have claimed that even the present levels of air pollution could lop off several years of the life-span in humans and animals. The efforts of the mandated institutions has not reversed the decline in Air Quality.

We should monitor, raise awareness among the public and pressure lax polluters responsible for major sources of air pollution. The emissions testing for vehicles has helped. Mitigation options are available for other sources and should be pursued. For example, it will be a blunder to add a new coal plant as coal is the worst option for emission. We need to learn from the then promises of “clean coal” at Norochcholai, the switch to outdated technology, the subsequent failure to monitor as required in the EIA, and the failures of the regulators under pressure on and of politicians.

In a time where COVID-19 threatens our respiratory health and has overloaded the health services especially related to respiratory ailments, monitoring and mitigation of air pollution must be a moral priority.

Comments

Post a Comment