The Mother Who Wants to Put Air Pollution on Her Daughter’s Death Certificate

Millions die each year from dirty air. The trauma of a 9-year-old London girl may bring the dangers home.

By Beth Gardiner

Ms. Gardiner is the author of the forthcoming “Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution.”

Ella Kissi-Debrah‘s school photo.

The Ella Roberta Family Foundation

LONDON — Dirty air kills millions of people around the world every year, but it can be hard to put a face on a danger so vast. Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah is fighting to do just that. The face she has in mind is her daughter’s.

Ella Kissi-Debrah was 9 when she died in 2013, after three years of asthma attacks so bad, they sometimes triggered seizures. In photos, her smile is broad and bright, her hair braided. She loved music and swimming, and dreamed of becoming a pilot.

Ella lived with her family just off London’s South Circular Road, a major thoroughfare that is clouded by the diesel fumes that make London’s air — like much of Europe’s — thick and foul-smelling. A scientist’s analysis found that many of her hospitalizations coincided with local pollution spikes.

Now Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah wants to put air pollution on Ella’s death certificate. On Jan. 11, the top legal adviser for England and Wales, Attorney General Geoffrey Cox, backed her application for a new inquest, and this week, her lawyer plans to petition the High Court to authorize it.

The coroner who originally investigated Ella’s death ruled she had died of acute respiratory failure, but made no mention of pollution. Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah did not know then what diesel fumes can do to young lungs. It was more than a year after Ella’s death that she first learned dirty air is a known asthma trigger. “It was like putting a picture together” as it finally began to make sense, she told me.

Air pollution has never appeared on a British death certificate, said Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah’s lawyer, Jocelyn Cockburn. If a new coroner amends Ella’s to note its role, he or she could also demand that the government take action to prevent future deaths. And the moral and political repercussions could be even wider.

This grieving mother’s fight holds a power far greater than its potential to clarify the cause of one family’s tragedy. It’s bigger than just London and Britain, too. In demanding that dirty air be written into the official record as having contributed to her loss, Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah wants to force us all to recognize a danger that is all around us, but which we have long chosen to ignore.

This danger is truly global, and it is a consequence of our decisions to remain dependent on dirty, deadly fossil fuels and our failure to force polluters — like Volkswagen and the other auto manufacturers whose brazen shattering of pollution limits has left so many Europeans breathing toxic fumes — to follow the rules.

It is not just that air pollution itself can be invisible. Its links to all manner of health woes — heart attacks and strokes, premature birth and dementia, among many others — while very real, are hard to make out. That is why getting it on a legal document as a contributing factor in the death of one child matters so much. The message would be unmistakable: This is not an abstraction.

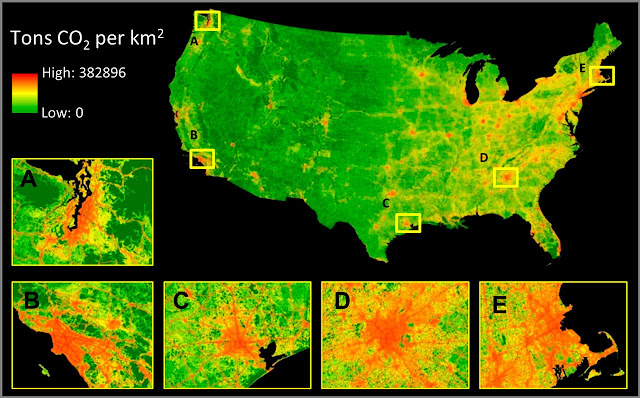

The numbers are chilling. Globally, air pollution cuts short seven million lives every year: about 40,000 in Britain, some 100,000 in the United States, and upward of a million each for China and India.

Europe’s air is significantly worse than America’s. That is in part because of Europe’s embrace of diesel cars, whose fumes are more noxious than gasoline’s. But the bigger reason is the failure of its governments to effectively enforce pollution rules. Instead, they have looked the other way while manufacturers sell diesels that emit six or more times legal nitrogen oxide limits.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency has been a more powerful policeman, turning rules on paper into air quality improvements that have saved millions of lives and trillions of dollarssince 1970. Of course, the E.P.A. and the regulations it enforces are under assault by the Trump administration and so decades of progress are at risk, and dirtier air and more ill health are the predictable consequences.

Few understand that better than Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debra, who was a secondary school teacher before Ella died. For a long time, she says, “I felt her death like a physical pain.” Now, she wonders how many other children London’s dirty air has killed since her own loss.

It does not have to be this way. Effective regulation can significantly reduce pollution levels. Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, is taking some meaningful steps, including charging the oldest and most polluting cars to enter the city’s center and retrofitting buses with filters.

But there’s only so much a mayor can do. The problem is much bigger than one city. Real progress requires action at the national, and European levels, to get the dirtiest diesels off roads, force carmakers to comply with the law and crack down on less obvious pollution sources, like household wood-burning. Ultimately, the real answer, in Europe and beyond, is eliminating fossil fuels altogether — andreducing the number of cars on our roads by providing better alternatives, such as strengthened public transportation and denser development that makes biking and walking easier.

And the science is clear. Cleaner air brings better health, and fewer deaths.

Only governmental power can fix this. So now Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah is running for London Assembly. And she hopes official acknowledgment, on a death certificate, of what pollution did to her daughter will make the need for action harder to ignore. “It’s not going to bring her back, obviously. But at least the real reason why she’s not here will be on there.”

Beth Gardiner (@gardiner_beth) is a London-based journalist and author of the forthcoming “Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution.”

By Beth Gardiner

Ms. Gardiner is the author of the forthcoming “Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution.”

|

Ella Kissi-Debrah‘s school photo.

The Ella Roberta Family Foundation

|

LONDON — Dirty air kills millions of people around the world every year, but it can be hard to put a face on a danger so vast. Rosamund Adoo-Kissi-Debrah is fighting to do just that. The face she has in mind is her daughter’s.

Ella Kissi-Debrah was 9 when she died in 2013, after three years of asthma attacks so bad, they sometimes triggered seizures. In photos, her smile is broad and bright, her hair braided. She loved music and swimming, and dreamed of becoming a pilot.

Ella lived with her family just off London’s South Circular Road, a major thoroughfare that is clouded by the diesel fumes that make London’s air — like much of Europe’s — thick and foul-smelling. A scientist’s analysis found that many of her hospitalizations coincided with local pollution spikes.

Now Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah wants to put air pollution on Ella’s death certificate. On Jan. 11, the top legal adviser for England and Wales, Attorney General Geoffrey Cox, backed her application for a new inquest, and this week, her lawyer plans to petition the High Court to authorize it.

The coroner who originally investigated Ella’s death ruled she had died of acute respiratory failure, but made no mention of pollution. Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah did not know then what diesel fumes can do to young lungs. It was more than a year after Ella’s death that she first learned dirty air is a known asthma trigger. “It was like putting a picture together” as it finally began to make sense, she told me.

Air pollution has never appeared on a British death certificate, said Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah’s lawyer, Jocelyn Cockburn. If a new coroner amends Ella’s to note its role, he or she could also demand that the government take action to prevent future deaths. And the moral and political repercussions could be even wider.

This grieving mother’s fight holds a power far greater than its potential to clarify the cause of one family’s tragedy. It’s bigger than just London and Britain, too. In demanding that dirty air be written into the official record as having contributed to her loss, Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah wants to force us all to recognize a danger that is all around us, but which we have long chosen to ignore.

This danger is truly global, and it is a consequence of our decisions to remain dependent on dirty, deadly fossil fuels and our failure to force polluters — like Volkswagen and the other auto manufacturers whose brazen shattering of pollution limits has left so many Europeans breathing toxic fumes — to follow the rules.

It is not just that air pollution itself can be invisible. Its links to all manner of health woes — heart attacks and strokes, premature birth and dementia, among many others — while very real, are hard to make out. That is why getting it on a legal document as a contributing factor in the death of one child matters so much. The message would be unmistakable: This is not an abstraction.

The numbers are chilling. Globally, air pollution cuts short seven million lives every year: about 40,000 in Britain, some 100,000 in the United States, and upward of a million each for China and India.

Europe’s air is significantly worse than America’s. That is in part because of Europe’s embrace of diesel cars, whose fumes are more noxious than gasoline’s. But the bigger reason is the failure of its governments to effectively enforce pollution rules. Instead, they have looked the other way while manufacturers sell diesels that emit six or more times legal nitrogen oxide limits.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency has been a more powerful policeman, turning rules on paper into air quality improvements that have saved millions of lives and trillions of dollarssince 1970. Of course, the E.P.A. and the regulations it enforces are under assault by the Trump administration and so decades of progress are at risk, and dirtier air and more ill health are the predictable consequences.

Few understand that better than Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debra, who was a secondary school teacher before Ella died. For a long time, she says, “I felt her death like a physical pain.” Now, she wonders how many other children London’s dirty air has killed since her own loss.

It does not have to be this way. Effective regulation can significantly reduce pollution levels. Sadiq Khan, the mayor of London, is taking some meaningful steps, including charging the oldest and most polluting cars to enter the city’s center and retrofitting buses with filters.

But there’s only so much a mayor can do. The problem is much bigger than one city. Real progress requires action at the national, and European levels, to get the dirtiest diesels off roads, force carmakers to comply with the law and crack down on less obvious pollution sources, like household wood-burning. Ultimately, the real answer, in Europe and beyond, is eliminating fossil fuels altogether — andreducing the number of cars on our roads by providing better alternatives, such as strengthened public transportation and denser development that makes biking and walking easier.

And the science is clear. Cleaner air brings better health, and fewer deaths.

Only governmental power can fix this. So now Ms. Adoo-Kissi-Debrah is running for London Assembly. And she hopes official acknowledgment, on a death certificate, of what pollution did to her daughter will make the need for action harder to ignore. “It’s not going to bring her back, obviously. But at least the real reason why she’s not here will be on there.”

Beth Gardiner (@gardiner_beth) is a London-based journalist and author of the forthcoming “Choked: Life and Breath in the Age of Air Pollution.”

Comments

Post a Comment