Sick and coaled: Kalpitiya villagers hit out at Lakvijaya apathy

By Sandun Jayawardana

- Coal dust causes respiratory problems and other health hazards to people near power plant

- Agreement signed after FR petition, but residents say CEB fails to abide by it

- Plant official dismisses the allegations and says measures are being taken to mitigate the problems

Dilani Dissanayake frets over the health of her one-month-old infant. The 37-year-old mother had endured a difficult pregnancy, which required a lengthy stay in hospital due to a respiratory illness. She and her husband, Sarath Gunasekara (42), are in no doubt as to its cause. “It’s all that dust from the plant,” Dilani said, referring to the Lakvijaya Coal Power Plant, situated several hundred metres from her home in a Kalpitiya village.

A mound of fly ash (above) and (inset left) a student shows his palm covered in Coal dust. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

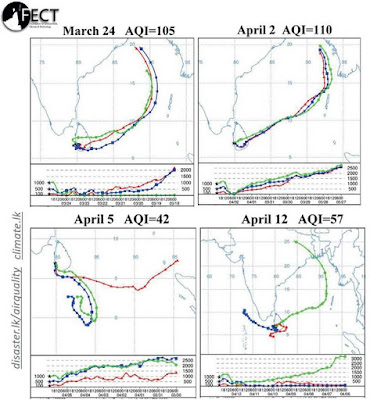

The dust that Dilani refers to comes from the plant’s coal yard. The yard on the landward side, residents say, continues to make their lives miserable, especially during the April-to-October monsoon season, when strong winds carry coal dust to adjacent villages.

The plant uses more than 2.2 million metric tonnes of coal every year for its three units, which together produce 900 megawatts of power. According to statistics posted on the Power and Energy Ministry website, 114 metric tonnes of coal are needed per hour for a 300 MW power plant.

Dilani filed a Fundamental Rights (FR) petition in the Supreme Court against the coal power plant in August, 2016. The petition was also signed by two residents representing the affected farming and fishing communities and the environmental organisation Environmental Foundation Limited (EFL).

“We are worried about our baby daughter’s health. After I explained the situation, officials from the plant met me two months ago and assured that they would pay rent for six months for us to move to a different house. They even asked me to start looking for a house and to submit a request letter along with a certificate from the Grama Niladhari. Though we submitted the documents, we are yet to get a response from them,” Sarath told the Sunday Times.

Dust particles from the coal yard stick to everything. Sarath, who is a farmer, pointed out that dust settles in coconut trees and vegetable crops. If allowed to accumulate, it can destroy both the trees and the crops. Washed clothes cannot be hung out to dry when there are strong winds as the dust sticks to them. This causes severe difficulties, especially for schoolchildren.

Sarath, who has two school-going sons, said the eldest was once punished by the school’s principal for not coming to school in his uniform. There was no uniform to wear that day as the clothes were covered with a layer of coal dust. The matter was resolved after the parents explained problem to the principal.

Respiratory illnesses are not the only health issues the residents face as a result of coal dust. Inoka Chathurangani (28), showed us the feet of her four-year-old daughter. The soles were smeared with dust that Inoka said collected on the floor of their house. Some time ago, blisters broke out on her daughter’s feet and the skin peeled away in places. This could be because of the dust, she said.

Meanwhile, both Inoka and her husband Leslie (34) have been prescribed eye drops for eye irritation. Several other villagers the Sunday Times spoke to also said they suffer from eye irritation. Inoka had no eye problems prior to moving to Norochcholai five years ago. She has been to hospital on three occasions since then to obtain treatment for her eye ailments.

Jayanthi Mallar (40), from Kilinochchi, lives in a house with seven other female workers from the north. They are among the many Northern Province people who work in the vegetable fields in Norochcholai.

Jayanthi said the money she earned as a day labourer helped her look after her parents and son in Kilinochchi. She told us that she found it difficult to send much money back, because much of what she earned was spent on medicines. Showing places where the dust has gathered throughout the house, she attributed her breathing problem and other health issues to coal dust.

Subsequent to the FR petition, the EFL in February this year signed an agreement with the Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB), the Public Utilities Commission of Sri Lanka (PUCSL) and the North Western Province Provincial Environmental Authority (NWPEA).

Vegetable cultivation next to coal power plant

Titled ‘Implementation Plan for the Mitigation of Environmental Impacts caused by the Norochcholai Coal Power Plant’, the agreement laid out a list of measures that had to be taken to minimise the environmental impact from the plant. A committee comprising representatives of these institutions, together with those from the local community and officials of the Lakvijaya plant, are expected to meet on a regular basis to monitor the implementation of the plan.

Accordingly, the Supreme Court has granted further time for all parties to enter into a settlement on the mitigatory environmental measures. The case is to be taken up again in October.

Against the backdrop of the Lakvijaya plant and its coal yard, community representatives held a media conference this week to say that they no longer believed that the CEB would honour the agreement. They charged that many of the measures stipulated under the agreement had not been implemented properly and that the CEB representatives were no longer attending progress review meetings.

M.C. Alexander (48) is a former Pradeshiya Sabha Chairman and a farmer by profession. He was also a signatory to the FR petition in the Supreme Court. He said all the petitioners had submitted affidavits, stating that the CEB was not following through on its earlier commitments. He acknowledged that some progress had been made. Problems connected to the fly-ash yard had been resolved to a great extent, he said. Nevertheless, many issues remain.

Mr Alexander said the depletion of water resources was another concern of the local community. When several million litres of ground water are used at the plant, from where are we going to find water for culitvation? Are we supposed to farm using sea water?” he asked.

Peter Thisera (63), President of a local fisher community association, said villagers were not calling for the plant to be closed down. “We just want the authorities to take measures to minimise the harm that the plant does to the community,” he said.

Dilani Dissanayake showing the difference between a curtain with coal dust and an unused one

“The CEB is making it difficult for us to breathe,” said farmer S.A. Sarath Pushpakumara (42). Mr Pushpakumara, a father of two, said the people wanted the government to take urgent measures to end their suffering, at least for the sake of their children.

Community leaders claimed that the CEB had disregarded a Moratuwa University recommendation that a proposed wind barrier around the coal dust yard should be raised to 30 metres. They said the CEB had decided to go ahead with the 15 metre barrier as had been originally planned. “The coal mounds can rise up to 15 metres in height. So, having a 15 metre barrier serves no purpose,” Mr Alexander remarked.

Dismissing these claims as baseless, a senior official at the Lakvijaya Coal Power Plant there said the CEB had not withdrawn from the agreement signed with the petitioners. “We have been given targets and time frames to achieve them. There are two different committees that monitor the progress. A committee headed by the District Secretary meets twice a month. We are attending those meetings,” he claimed. He, however, said the officials were not prepared to meet “every other day” with various representatives when they had a lot of work to do.

He said the CEB was not prepared to go in for a 30-metre wind barrier as it would be costly. The 15-metre barrier alone would cost more than Rs 700 million. “The board cannot spend several billion rupees based on a recommendation alone, especially knowing that the wind barrier is only part of the solution,” he argued.

The official said the authorities had installed many new sprinkler systems at the plant to douse the coal with water to minimise the dust particles being carried away by the wind. He pointed out that, by using a mixture of chemicals and water, they had been able to mostly resolve a similar issue at the fly-ash yard. “The wind barrier will take time, but after its installation at the coal yard, it will help resolve the problem to a great extent,” he said.

Comments

Post a Comment